Laos - Ink Drawings

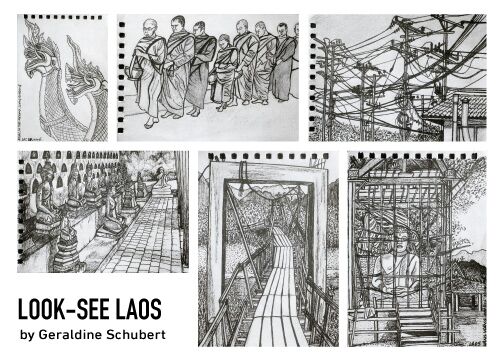

LOOK-SEE LAOS

Scenes of Laos and Southeast Asian Nagas, ink drawings on paper

Solo exhibition, Utterly Art, March-April 2018

Guest of honour: Mr Sonexay Vannaxay

Minister Counselor and Deputy Chief of Mission, Embassy of the Lao PDR

Scenes of Laos and Southeast Asian Nagas, ink drawings on paper

Solo exhibition, Utterly Art, March-April 2018

Guest of honour: Mr Sonexay Vannaxay

Minister Counselor and Deputy Chief of Mission, Embassy of the Lao PDR

In December 2014, I visited Laos. It was a trip of 'returns': a return to travelling alone after not having done so for a long time, a return to travel sketching, a return to the very basics of art...the sweetest return was when one of my images from this trip received an award in the Established Category at the United Overseas Bank Painting of the Year 2015.

Equipping myself with merely pencil, pen and sketchpad in Laos was not so much a matter of convenience as it was an artistic decision. Twenty-five years of practice had made techniques second nature and I wanted to recall them.

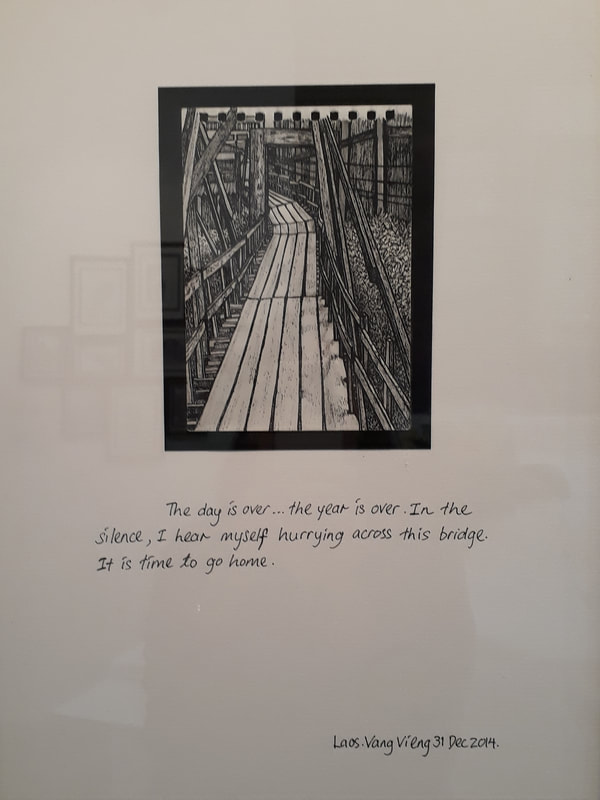

From Vientiane through Vang Vieng to Luang Prabang and back, I studied and rendered whatever caught my attention, in the grey of graphite, the black of ink and the white of paper. Simplifying my medium and support gave me renewed appreciation of art-making; once again, I became aware of the contrasting shapes, varying lines, nuances of tone... the building blocks of artwork. I felt inspired by a reignited sense of wonder.

In an age where images are consumed and discarded in haste, my hope for this body of work is to engage and sustain the viewers' interest as they delight in the images as a whole and also carefully observe the detail in each drawing - to SEE and LOOK at Laos.

In an age where images are consumed and discarded in haste, my hope for this body of work is to engage and sustain the viewers' interest as they delight in the images as a whole and also carefully observe the detail in each drawing - to SEE and LOOK at Laos.

The Nagas of Southeast Asia

The Naga / river serpent is found in the mythology and royal tradition of Southeast Asia even before the advent of Hinduism and Buddhism. Intrigued by the symbolism of the Naga and how it appears across Southeast Asia oblivious to borders, I tracked it across eight countries in the region, namely Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

Many in the region revere Nagas, especially those who flank rivers: the water people, like those who live along the Mekong, the Ayeyarwady, the Menam Chao Praya, the Nam Khan and the Tonle Sap. To these people, Nagas are water gods to be venerated. The Naga embodies protection for all in the region who believe in it. Easily angered by human stupidity and greed, Nagas have to be appeased with offerings to maintain the eternal bond between humans, gods and rivers, connecting heaven and earth.

Often depicted as wise and great serpents or dragons, there are numerous interpretations proving that the Naga does not belong to just one country but instead evidencing an instance of cultural and religious interchange and overlap. While the Naga story and appearance may vary, essentially, the Naga reflects our collective history and shared culture.

Offering continuity between past and present, it is interesting to see how from mainland to island Southeast Asia, the Naga is such an important element in all these societies. And it is fascinating how a symbol like this can be interwoven into people's lives even today.

Given the divisive climate, Nagas serve as a powerful reminder that we were once fellow writers of a common narrative.

The Naga / river serpent is found in the mythology and royal tradition of Southeast Asia even before the advent of Hinduism and Buddhism. Intrigued by the symbolism of the Naga and how it appears across Southeast Asia oblivious to borders, I tracked it across eight countries in the region, namely Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

Many in the region revere Nagas, especially those who flank rivers: the water people, like those who live along the Mekong, the Ayeyarwady, the Menam Chao Praya, the Nam Khan and the Tonle Sap. To these people, Nagas are water gods to be venerated. The Naga embodies protection for all in the region who believe in it. Easily angered by human stupidity and greed, Nagas have to be appeased with offerings to maintain the eternal bond between humans, gods and rivers, connecting heaven and earth.

Often depicted as wise and great serpents or dragons, there are numerous interpretations proving that the Naga does not belong to just one country but instead evidencing an instance of cultural and religious interchange and overlap. While the Naga story and appearance may vary, essentially, the Naga reflects our collective history and shared culture.

Offering continuity between past and present, it is interesting to see how from mainland to island Southeast Asia, the Naga is such an important element in all these societies. And it is fascinating how a symbol like this can be interwoven into people's lives even today.

Given the divisive climate, Nagas serve as a powerful reminder that we were once fellow writers of a common narrative.